|

Chapter 1

It

is just over a century since the Labour Party first achieved

parliamentary representation in the area which is now covered by our

Constituency Party.

In

1909 our current Labour Party branches were spread amongst no less than

three separate Parliamentary Divisions. Dramatically in that year and

without a General Election being held, all three seats went to Labour.

It

was all due to the role of the Miners’ Union. 1909 was the year in

which they first affiliated to the Labour Party, following a national

ballot.

Two

statues can be seen outside the former Miners’ Offices on Saltergate in

Chesterfield. One of these is of James Haslam who was Secretary of the

Derbyshire Miners. The other is William Harvey who was their Financial

and Corresponding Secretary.

The

two were known as the “twin pillars” of the Derbyshire Miners’ Union

and they became MPs. Haslam was first elected in 1906 and Harvey in a

by-election the following year. Yet they were elected with the support

of the Liberal Party and were known as Lib-Lab MPs.

It

was when the Miners’ Union moved into the Labour Party that they broke

their links with the Liberals and joined the Parliamentary Labour Party

where they played prominent roles. They both stood successfully in the

two General Elections of 1910 as Labour candidates.

James

Haslam was the MP for Chesterfield, which at that time covered the area

of our current branches at Clay Cross, Tupton, Grassmoor, West and

Holmewood. William Harvey was the MP for a seat called North Eastern Derbyshire which included Dronfield, Eckington. Killamarsh and North Staveley.

North

Wingfield was part of a further constituency called Mid-Derbyshire. It

also went Labour in 1909 when a by-election was held. In the days in

which MPs weren’t paid, the Derbyshire Miners could not afford to run a

third candidate, so the Nottinghamshire Miners stepped in and ran their

Agent as the Labour candidate.

He was George Hancock, who was the first miner in England ever to be elected as

a Labour MP. For he had not emerged via the Lib-Lab avenue. The

legendary Labour leader Keir Hardie canvassed in the by-election.

Haslam,

Harvey and Hancock set a tradition going, which has led to the bits and

pieces which came together as NE Derbyshire all being represented by

Labour for a minimum of 88 years out of the past century.

Chapter 2

The next time you get a chance; have a look at the two statues outside the former Miners' Offices at Saltergate in Chesterfield.

The

one on your right is that of James Haslam. He was born in Clay Cross in

1842, the youngest of 10 children and he started work there on the pit

brow when he was ten years old, working 12 hours a day. He became the

Secretary of the Derbyshire Miners' Association (DMA) when it broke away

from the South Yorkshire Miners' Association in 1880 and helped to

build it up into a powerful organisation. He became the MP for

Chesterfield in 1906 which in those days also covered the areas of our

current Branches at Clay Cross, Grassmoor, Holmewood, Tupton and

West. He died in 1913. During his time as MP he continued to hold his

post with the DMA, for MPs were not paid until 1911 and then only

modestly.

The

statue on you left is that of William Edwin Harvey, who had a similar

background to Haslam. He was born in 1852 in Hasland and went to work

at a pit at Grassmoor when he was ten. Both Harvey and Haslam worked

closely together on trade union matters and were also both active as

Primitive Methodists. Harvey became MP for what was then known as North

Eastern Derbyshire at a by-election in 1907 and held the position until

his death in 1914. He held various posts with the DMA such as Treasurer,

Assistant Secretary and finally the joint positions of Financial and

Corresponding Secretary. His seat included the areas of our current

Staveley, Killamarsh, Eckington and Dronfield Branches.

Haslam

and Harvey were known as the "twin pillars" of the DMA. They were both

elected initially as LIb-Labs (i.e. as labouring people who were trade

unionists but obtained organisational and financial backing from the

Liberal Party). But the DMA was by that time affiliated to the Miners

Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) who in 1908 held a ballot on whether

to affiliate to the recently established Labour Party. When the Miners

voted to do this, Haslam and Harvey then moved over to become Labour

MPs, winning their seats under that label in two subsequent General

Elections that were held in 1910.

James Haslam MP

William Harvey MP

They were also prominent figures in both the MFGB at national level and the Trade Union Congress.

If

you wish to find out more about Haslam and Harvey, the best source of

information is contained in a book entitled "The Derbyshire Miners" by

J.E. Williams, published by George Allen and Unwin in 1962. As it is

993 pages long, your best bet would be to borrow it from your local

library. If they don't have it they can easily get hold of a copy for

you. It has a full index which can be used to sort out the best

references to Haslam and Harvey. At page 320 there is a photograph of

the unveiling of the two statues outside the Miners' Offices on 26 June,

1915 - although the huge crowd is easier to see in the photo than are

what were then two very new white statues.

Chapter 3

For

numbers of years prior to 1918, the current territory covered by the NE

Derbyshire Constituency formed parts of three different Parliamentary

seats. I explained in an earlier article how these all came under

Labour control in 1909. Yet by 1915 Labour had lost control of all of

them.

First

of all, James Haslam the Labour MP for Chesterfield died in 1913. The

Derbyshire Miners selected Barnet Kenyon to stand in his place. He had

held posts as President, Assistant Secretary and General Agent for the

Derbyshire Miners’ Association. But because of his close links with the

Liberal Party both the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party

and the Miners‘ Federation of Great Britain refused to endorse him as a

candidate. The Miners spending a whole day discussing the issue at their

national conference. Kenyon was, however, elected unopposed at the

bye-election. At that time Clay Cross and much of the area around it

(apart from North Wingfield) formed part of the Chesterfield seat.

In

1914, William Harvey the MP for North Eastern Derbyshire (which covered

Dronfield and surrounding areas) also died. Labour ran James Martin as

their candidate in this bye-election. He was President of the Derbyshire

Miners at the time. Yet he finished bottom of the poll in a three

cornered fight. The reasons for this were (1) the Liberals split the

anti-Tory vote by running a candidate for the first time since 1907, (2)

the miners themselves were being offered conflicting patterns in the

area by the Liberal Kenyon and Labour’s Martin, (3) with the first

world war starting in1914, patriotism was to the fore and the seat was

won by the Conservative Major Bowden who had a majority of 314 over the

Liberal and (4) Labour had little organisation and had previously

depended upon the personality and prominence of the late William Harvey.

After a defeat in which Labour obtained less then 27% of the vote,

Labour quickly set up a constituency-style organisation. This was

something of a pioneering move as the Labour Party nationally did not

set up its general constituency structure until 1918.

The third

seat which was lost was Mid-Derbyshire which covered North Wingfield.

George Hancock of the Nottinghamshire Miners was their MP. But in 1915

he defected to the Liberal Party. Although Kenyon remained as MP for

Chesterfield until 1929, it was Labour who started to dominate the

political scene in the area covered by our current constituency. This

was helped by boundary changes in 1918. Our area came to be divided

between what was to be the solid Labour seat of Clay Cross (which then

included North Wingfield) and a redrawn North Eastern Derbyshire which

was taken again by Labour in the 1922 General Election in dramatic

circumstance.

Labour

burst onto the local political scene in 1909 when the Derbyshire

Miners’ Association (DMA) joined the Labour Party and the three

parliamentary seats which cut into the current boundaries of NE

Derbyshire each acquired a Labour MP. Yet due to two deaths and a

defection, Labour had lost all three seats by 1915 and it was not until

1922 that it was again successful.

Chapter 4

New

parliamentary boundaries and the first votes for women were introduced

in 1918. The three seats which cut into our current Constituency

Boundaries were then Chesterfield, North Eastern Derbyshire and Clay

Cross.

Until

1929, the Chesterfield Constituency (which included the arrears of our

current West Branch, Grassmoor and New Whittington) underwent one of its

periods of Liberal control. This occurred because their MP Barnet

Kenyon defected to the Liberals, although he had been a leader of the

DMA.

The

Clay Cross Constituency contained an area dominated by pits, including

North Wingfield, Tupton, Holmewood, Pilsley, Stonebroom and Clay Cross

itself. Frank Hall of the DMA stood in 1918, taking 45.9% of the vote.

He lost due to the fact that the Tories united behind a Liberal

Coalition candidate who supported the continuation of the Lloyd George

Coalition after the war. A victorious Coalition which came to be

dominated by Conservatives.

Labour,

however, took the seat in 1922 and it became one of the strongest

Labour seats in the country until its abolition in 1950. When Labour

suffered a massive collapse in 1931 following the economic crisis and

Ramsay MacDonald its leader defecting to form a National Government,

Labour still held Clay Cross by 9,552. This was a considerable majority

as the Labour Party nationally lost no less than 236 out of 288 seats.

In

this period, North East Derbyshire incorporated Dronfield, Eckington,

Killamarsh and Staveley. It also spread over into Clowne, Barlborough,

Bolsover and areas which were later moved into Sheffield. In dramatic

circumstances it went Labour in 1922. The Labour candidate Frank Lee was

an official of the DMA. He failed narrowly to take the seat in 1918,

when he stood as one of the early advocates of the nationalisation of

the coal industry.

The

contest of 1922 could not have been closer. Recounts took place. On the

second count Labour’s majority was two. After the sixth recount, the

boxes were sealed and. fresh counting clerks were employed. This still

did not resolve the matter. As there was still no agreement about the

result, it went before the King’s Bench Division of the Courts. Lee was

belatedly declared the winner by 15 votes and entered the Commons five

months after the count.

In

all Frank Lee fought 7 General Elections for Labour, losing in 1918 and

again in 1931. He served a total of 16 years as an MP until his death

in 1942. When Chesterfield finally returned to Labour in 1929 with the

election of George Benson he went on to serve as their MP for a total of

no less than 31 years in spite of his defeat in 1931.

Chapter 5

The

Clay Cross Parliamentary Constituency operated from 1918 and ended with

the 1950 General Election. It covered Clay Cross, Tupton and North

Wingfield in our current Constituency, plus areas in an around

Holmewood, Glapwell, Shirebrook and Stonebroom. Mining abounded.

Yet

although the Constituency Labour Party was dominated by the miners’

vote, out of the six different Labour candidates it ran for parliament

at various elections only two of these were miners. This showed an

independence of mind by local miners from the pressures of the

leadership of the Derbyshire Miners which was aided by the influences of

Methodism and mobilised socialist views. The later coming from the

local influence of bodies such as the left-wing Independent Labour

Party, which only ended with its disaffiliation from Labour in 1932.

The seat also became rock-solid Labour, so it attracted the interest of leading Labour figures at national level.

Yet

the first election of 1918 followed a conventional pattern for the

area. Fred Hall, the Labour candidate was a leading official of the

Derbyshire Miners Federation who eventually served on the Federation’s

national executive committee for 29 years. He was, however, the only

Labour candidate who failed to win the seat. He lost by 1,221 to a

Liberal who had Conservative backing. A year after the Russian

Revolution, they wanted to keep out what they saw as Bolsheviks.

When

Fred Hall dropped out of standing for the seat just prior to the 1922

General Election, Charlie Duncan was selected in his place. He had

helped to found the Workers’ Union who had been involved in the birth of

the Labour Party and which represented unskilled workers. He had

previously had a spell as the Labour MP for Barrow and had served as

both Whip and Secretary of the Parliamentary Labour Party.

He

won the elections in Clay Cross in 1922, 1923, 1924, 1929 and 1931. His

final success revealed how Labour had built up the seat. The 1931

election was held following the collapse of the minority Labour

Government in the middle of a major financial crisis, with Ramsay

MacDonald its leader defecting to run a National Government. Labour’s

position at the subsequent General Election collapsed from 288 to 52

seats, yet Labour held Clay Cross by almost 10,000 votes.

When

Charlie Duncan died in 1933, Clay Cross adopted Arthur Henderson as

their candidate. Known as “Uncle Arthur” he is a huge figure in the

early history of the Labour Party. He was leader of the Labour Party

from 1908 to 1910 (with another spell at the start of the First World

War). He served as Labour’s first Cabinet Minister in First World War

Coalitions from 1915 to 1917. He helped shape the pre-Blairite structure

of the Labour Party as General Secretary of the Labour Party, a post he

held from 1912 to 1935. He was Home Secretary in the first Minority

Labour Government of 1924 and Foreign Secretary from 1929-31. When

MacDonald defected he took over as temporary leader until 1932, but gave

up the position because he had by then lost his parliamentary seat.

Clay Cross provided his avenue back into Labour’s parliamentary

politics.

In

the by-election one of his opponents was Harry Pollitt the General

Secretary of the Communist Party who lost his deposit with 10.8% of the

votes to Henderson’s 69.3%.

Whilst

MP for Clay Cross, Henderson went on to receive the Nobel Peace Prize

and was held in high regard as “no-one ever sought his help in vain*”.

He died in 1935.

At

the subsequent General election, Clay Cross ran the 35 year old Alfred

Holland a local Methodist. But within 10 months he was stricken with

spinal meningitis and died shortly afterwards.

A

by-election in 1936 led to the Clay Cross Labour Party running its

fourth candidate in five years. George Ridley had been on the Executive

of the Railway Clerk’s Association since 1909. He was seen as “becoming

the Labour Party’s leading pamphleteer*”. In 1944 he also died whilst

still an MP.

After

26 years, Clay Cross once more adopted a Derbyshire Miners’ Candidate

in Harold Neal the area’s Vice President, who went on to become

Secretary of the Miners’ group of MPs in parliament. There was a

war-time pact amongst Churchill’s War-time Coalition Government at the

time, so only two independent candidates stood against Neal. One ran as a

“Workers Anti-Fascist” and the other as an “Independent Progressive”.

Neal got 76.3% of the votes. When the war ended, he improved his

position by taking 82.1% of the votes in opposition to a Conservative.

When

the boundaries were redrawn and the Clay Cross seat was absorbed into

other areas, Harold Neal became the Labour MP for Bolsover. He had a

period as Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Fuel and Power in

1951 and retired as MP in 1970 to be replaced by Dennis Skinner who was

the Chair of NE Derbyshire Labour Party in the period up to then, being a

member of the Clay Cross Labour Party.

A

souvenir brochure published by the Clay Cross Divisional Labour Party

in 1948 pointed out Labour’s dominance in the area, stating that there

were “46 Local Government Seats (exclusive of Parish Councils) within

the Constituency : of these 40 are held by Labour members. In addition,

there are 16 Parish Councils : in the majority of cases we have 100 per

cent representation”. ( * = The two earlier quotations are also taken from this invaluable source).

Chapter 6

From

1918 to 1950 our corner of Derbyshire contained three parliamentary

seats; two of these differed considerably from the current structures.

The seat that we would still recognise is that of Chesterfield, which

was based on its municipality although it also lapped beyond this.

One

of the seats was the Clay Cross Division which (as described in my

previous article) was powerfully held by Labour from 1922 onwards. In

fact it was one of the strongest Labour seats in the country and was

held comfortably even in 1931 although the Labour vote then collapsed

nationally.

Next in Labour’s mining strength came what was known as the North Eastern

Derbyshire Division. It included what is now the northern section of

the Bolsover District centred on Clowne, much of Staveley, areas later

transferred to Sheffield such as Beighton and Dore, plus Dronfield,

Eckington and Killamarsh. This was also mainly mining territory (but not

exclusively so). Labour gained the seat by only 15 votes in 1922,

losing it afterwards only in the 1931 collapse.

Whilst

the Chesterfield Division took in mining territory such as Grassmoor

and Arkwright and housed the offices of the Derbyshire Miners, its

municipal character plus its business and commercial elements and its

engineering works supplied it with countervailing tenancies to the solid

mining tradition.

I

have previously explained how Barnet Keynon although emerging as an

official of the Derbyshire Miners Association took the seat for the

Liberals in 1918, 1922, 1923 and 1924. It was only when he retired in

1929 that Labour took the seat under George Benson. Yet the seat was

again lost in the collapse of 1931, returning to Labour from 1935.

Chesterfield’s

Labour links with MPs who came from the mining industry were sparse.

James Haslam fitted the category between 1909 and 1913. The next person

to meet the criteria was Eric Varley much later in 1964.

Chapter 7

The

Clay Cross Constituency, the old North Eastern Derbyshire Constituency

and a more recognisable Chesterfield Constituency, all existed alongside

each other from 1918 to 1950. It was a period of great political

change and social turmoil.

The 1918 Election took place just

after the end of the First World War in which many local people had

fought, including those under conscription which had extended to Coal

Miners. The election took place following the operation of a post-war

Coalition in which Labour had been involved. The Liberals and

Conservatives, however, attempted to keep their relationship going when

the war ended. In the bulk of seats, they did not run candidates against

each other. Lloyd George as Prime Minister and a Liberal was the main

architect of the move.

Although the deal between the Liberals

and the Conservatives worked in the short run and they were back in

Government, it eventually aided social forces through which Labour was

coming to be seen as the alternative to the Conservatives. It was the

start of a steep decline in support for the Liberal Party. It has some

lessons for the current Con-Dem Coalition.

The social tension of

the time was seen in two huge strikes in the Coal Industry in 1921 and

1926. The latter being linked to the General Strike, but which went well

beyond it. Labour had electoral victories a few years after both of

these strikes. In 1924 they formed the first minority Labour Government.

It produced what became known as the Wheatley Housing Legislation which

enabled Labour Local Authorities in particular to build Council Housing

Estates - a massive housing improvement for many. Then a minority

Labour Government operated from 1929 to 1931.

This second

Government was hit by the international financial crisis. Ramsay

MacDonald was Prime Minister during the time of both these Minority

Labour Governments, but he moved from the Labour Party with a small band

of defectors in 1931 to set up a coalition Government (known as the

National Government) with the Conservatives and a section of the divided

Liberal Party. Once more an election was soon called and "National"

candidates from the Conservatives, elements of the split Liberal Party

and the small group of "National Labour" won a massive victory. But

although Labour lost huge numbers of seats (but not Clay Cross), they

started the recovery in the 1935 election - including in our wider area.

Following

the experiences of the Second World War and a widespread determination

not to return to the poverty, unemployment and depression of the

inter-war years, Labour won the 1945 election under Clem Attlee with a

huge majority of 147. All three of our local seats returned solid Labour

majorities. Although Labour achieved the establishment of a Welfare

State with a National Health Service, a public ownership programme with

major significance locally because of the Nationalisation of the Coal

Mines in 1947, plus an era of full employment and fair-shares for all;

its majority in the 1950 election dropped to only 5.

The contest

in 1950 was fought under a new local constituency structure. Clay Cross

and the old North Eastern Derbyshire being replaced by Bolsover and a

new North East Derbyshire which formed the basis of our current

constituency set-up. The later formed a familiar "C" shape around

Chesterfield. There have been many chops and changes since to Bolsover,

NE Derbyshire and Chesterfield, but the only major area to be lost from

their common external boundaries was an area transferred from NE

Derbyshire to Sheffield in 1970. In 1950 Labour recorded huge

majorities in the three seats in the area - 25,833 in Bolsover, 16,683

in Chesterfield and 16,457 in NE Derbyshire. The combined majority was

nearly some 59,000 and almost 9,000 greater than the total in 1945. This

is partly explained by the fact that the 1945 election wasn't fought on

an up-to-date register.

The huge dominance of Labour in our area at

the time arises from the dominance of mining communities and the

collective spirit they generated around 1950.

Chapter 8

From

1918 to 1950 three seats ran roughly from east to west across our area.

NE Derbyshire to the north, Chesterfield in the centre and the Clay

Cross Constituency to the south.

The

1950 General Election was, however, fought on new parliamentary

boundaries which we would recognise today. The Bolsover Constituency was

established and the Clay Cross seat was disbanded. North East

Derbyshire (rather than the “Eastern” variety) came into existence. Clay

Cross with Tupton and North Wingfield (also taken from the Clay Cross

Division) become part of the newly structured NED Seat whose boundaries

were initially similar to those of the current NE Derbyshire District

Council area and included places such as Stonebroom.

At

the 1950 Election, Labour easily took all three of the new seats.

Harold Neal the former Clay Cross MP won the Bolsover seat by 25,833.

Harry White moved from the old NED seat to the new one, with a majority

of 16,451. Whilst George Benson carried on at Chesterfield with a

majority of 16, 683. The late Bas Barker who will be remembered by many

of us for his work in the Trade Union Movement and then with Pensioners,

taking only 554 votes for the Communist Party. Benson also had had a

left-wing background, having at one time been Treasurer of the

Independent Labour Party which had been founded by Keir Hardie and

others. It had participated in the formation of the Labour Party itself.

The

current basic shape of our own Constituency came into operation for the

1950 election. The make-up of the area differed significantly from what

we know today. A large number of pits were in operation, whilst

Dronfield and Wingerworth were much smaller places than they now are.

Between 1950 and 1970, the Constituency was almost identical to that of

the area of the North East Derbyshire District, which at that time

contained what are now areas of Sheffield such as Mosborough and

Beighton as well as areas that are still part of the District including

Stonebroom, Holmewood and Pilsley. It was essentially made up of working

class communities which each had a close social bond.

From

1950 up to 1987 the Constituency continued the tradition of being

represented by Derbyshire Miners. The first of these was Henry White,

who had also represented the area under its old boundaries since 1942.

He came from Cresswell, served as a Miners' Branch Secretary for 18

years, became a Derbyshire County Councillor and an Alderman and was

appointed as Vice-President to the Derbyshire Miners' Association in

January 1939. He was first returned to parliament in 1942 following the

death of Fred Lee whom he had acted as Agent to for in the previous 1935

General Election - there being no General Elections held during the

Second World War.

Henry

White was successful in the General Elections of 1945, 1950, 1951 and

1955. The last three of these being held under the new boundaries. His

respective majorities in the new seat were between 16,451 and 17,344.

They reveal the power of the votes of mining families in these contests.

Such majorities were obtained although Labour lost the General

Elections of 1951 and 1955. His parliamentary contributions often

centred on coal mining concerns, such as an opposition to opencast

mining operations. Serving in parliament from 1942 to 1959 he saw a

period of what was called "war socialism" with its fair-shares policy

based upon rationing, then he saw the establishment of a post-war

welfare state and a mixed economy which the 1951 to 1959 Conservative

Government's felt a need (in the main) to accept.

He

was succeeded as our MP by Tom Swain, who was a powerful personality

and will be remembered by numbers of current activists in the

Constituency. His career will be dealt with next.

Chapter 9

Tom Swain was the Labour MP for North East Derbyshire from 1959 to 1979. Even

when we add the pre-1950 constituency set-up to the basic area we know

today (thus taking us back to 1885), then Tom remains the MP with the

longest period of service. Furthermore his majority of almost 20,000 in

1966 is the highest of any.

Tom's

record breaking is highly appropriate, as he was a larger than life

character. At one time he was a fair ground boxer and some would say

that he always looked the part. In the Commons Norman Tebbitt made a

remark which offended him and he shouted out “If you say that outside,

I'll punch your head in.” Sensibly, Tebbitt stayed put.

Tom

had ten children and five greenhouses. He had an ability which other

back-bench MPs envied. He could get prominent coverage in the press,

much to the delight of his constituents. In 1976 at the age of 66 he

twice put to flight teenagers who were harassing women – at Chesterfield

Station and also on the London Underground. The Sunday Mirror gave him

full page coverage under a banner headline calling him “The Ladies

Champion”, with four photos of Tom showing reconstructions of him

adopting the“”Chinny Grip” he had used to control the young thugs.

Tom

had worked in the pits for 34 years and came to hold a variety of posts

with the Derbyshire Miners, including Vice-President. His pugnacious

style led him into conflict with Tory grandees, especially in the mutual

conflict between Sir Gerald Narbarro and himself. Sir Gerald always

turned up at Budget Day dressed as a dandy with a top hat, so Tom turned

up wearing a pit helmet. Then at Prime Ministers” Questions to Harold

Wilson, concerning building a statue to Winston Churchill, Tom asked if a

statue could also be provided of Sir Gerald in Parliament Square to

frighten away the pigeons.

Yet

Tom fought seriously for his constituents, starting from his maiden

speech in a debate on the Coal Industry. Such speeches are expected to

be non-controversial, but that

wasn't Tom' style. He said that if he had attempted to be

non-controversial, it would have been his first time ever. In a later

speech he dealt compassionately with mining accidents, his own father

having been killed in the pit. When

in 1972, the Labour Councillors of Clay Cross refused to implement the

Housing Finance Act (which hiked up Council Rents and started the

destruction of Council Housing), their struggle gained widespread

publicity. In defending them in the Commons, Tom said “I now come to the

new centre of Europe – Clay Cross”.

Tom

was due to stand down as MP, but before the appropriate General

Election took place he was killed in a car crash. The mini he was

driving was hit by (of all things) an NCB lorry as he was travelling

along Woodthorpe Road to Mastin Moor. As well as this being a personal

tragedy, it turned out to have a serious impact on British politics. Tom

was killed on 2 March. On 28 March the Callaghan Government lost a vote

of confidence in the Commons by a single vote. If Tom had been alive,

his vote would have tied the outcome and the Speaker (by convention)

would have given his casting vote to the Labour Government. Instead a

General Election had to be held, leading to Thatcher first becoming

Prime Minister. As Tom had perceptively said to Thatcher in an

intervention shortly before his death, Labour had not yet shot its fox.

Chapter 10

The

current recommendations of the Boundary Commission would return the

North East Derbyshire Constituency to the shape it enjoyed between 1970

and 1983. For the 20 years before that, the area had also included

territory such as Mosborough and Beighton which were transferred to

Sheffield prior to the 1970 General Election.

Tom

Swain was MP when the change took place. As explained in Chapter 9, he

was due to retire in 1979, but he was killed in an accident shortly

before that year's General Election. He was replaced by Ray Ellis who

had worked at the High Moor pit in Killamarsh for 41 years, much of the

time underground. Ray became Secretary of his local Miners' Lodge and

then President of the Derbyshire NUM. When he attended the Derbyshire

Miners' Day Release Classes he became known as “Educated Ellis” and

during the 1983 General Election he was given to quoting from his

favourite philosopher Santayana when he addressed public meetings. He

served as Secretary to the Miners' Group of MPs during the 1984 strike

and spoke in support of the Miners' case in the Commons.

For

the 1983 General Election, however, the Constituency Boundaries

underwent a further change. Stonebroom, Morton and Pilsley were

transferred to the Bolsover Constituency, whilst Barrow Hill and Mastin

Moor were added from the Chesterfield Constituency. In the context of

the times, this was an advantage to Labour, as Barrow Hill and Mastin

Moor were then solid Labour areas. It was just as well that the change

occurred, for Ray only held onto the seat in 1983 with a majority of

2006. He had suffered from the nationwide swing against Labour in 1983.

This had resulted from a split in the Labour Party which led to a

challenge from the Social Democratic Party led by Roy Jenkins who had

been a former Labour Deputy Leader and Home Secretary. Nationally Labour

ended up with its lowest percentage vote since 1918.

As

mining went into decline in North Derbyshire, Ray was to be the last

local miner to enter the ring as a new Labour MP. He was preceded by the

late Eric Varley who was first selected to stand for Labour for the

1964 General Election for Chesterfield and Dennis Skinner who became MP

for Bolsover in 1970. Dennis originates from Clay Cross and had been

Chairman of the North East Derbyshire Constituency Labour Party prior to

becoming on MP. After 41 years, he still represents Bolsover in

parliament.

In

all, ten Derbyshire Miners have been local MPs since James Haslam was

first elected in 1906. In the next chapter we will examine the overall

contribution of these pitmen politicians over more than 105 years.

Chapter 11

For

most of the 106 years since 1906, this area has been represented by one

or more MPs who originated as coal miners and had been officials of

their local miners' lodge and/or of the Derbyshire Miners Association.

In all, there have been ten such MPs. Anyone born in the area who is now

a pensioner could well have come across six of these. I deal with these

below in pairs.

The

local mining MP Henry White retired in 1959, then Harold Neal retired

in 1970. They had both been returned to parliament via by-elections

during the Second World War and participated in the legislation to

fulfil a long-time aim of the miners – the nationalisation of their

industry, which became operative in 1947. Harold Neal was then the MP

for Bolsover. Appropriately, he later became Parliamentary Secretary to

Philip Noel-Baker the Minister for Fuel and Power. Henry White was the

MP for North East Derbyshire and both his first and final contributions

in the Commons were typical of him, in being about the mining industry.

Henry

White was succeeded by the miners Tom Swain and then Ray Ellis. Tom was

a larger than life character, who after 20 years as an MP was killed on

the Norbriggs to Woodthorpe Road when a Coal Board lorry ran into the

mini he was driving. This was both a personal and political tragedy.

Four weeks after his death, the Callaghan Government lost a vote of

confidence by a single vote and this led to the General Election of 1979

which brought Margaret Thatcher to power. If Tom hadn't been killed,

the vote of confidence would have ended in a tie and by precedent the

Speaker's casting vote would have gone to the Callaghan Government and

the General Election would not have been called. Tom was followed by Ray

Ellis who became Secretary of the Miners' Group of MPs during the 1984

Miners' Strike and used avenues inside and outside of the Commons to

argue their case.

Eric

Varley and Dennis Skinner are the two remaining post-war mining MPs.

They were both MPs in early 1974 when the miners followed up a

work-to-rule over poor wages, with a strike. In response the Heath

Government instigated a three-day-working week to save fuel and then

called a General Election under the slogan “Who Governs Britain?”. The

electorate decided that the answer to the question was not to be the

Conservatives. A minority Labour Government then acted quickly to settle

the strike, aided by appointing Eric as a former miner to the post of

Secretary of State for Energy. Eric later became Secretary for State for

Industry, eventually resigning his seat in 1984 prior to that year's

protracted miners' strike. Dennis Skinner as the MP for Bolsover was a

leading figure both inside and outside of parliament on the side of the

miners in the major disputes of 1972, 1974 and 1984-5 as well as in

struggles against the privatisation of the coal industry and against the

final closure of deep mine pits in Derbyshire. Dennis remains fully

active in parliament today, but will almost certainly be the last pitman

MP from Derbyshire.

A

characteristic of all the above six post-war pitmen politicians is that

they were all firmly Labour MPs. But the four earlier DMA

parliamentarians came from a different era and differed from this clear

pattern.

Our

first two miners' MPs were James Haslam and William Harvey whose

statues stand outside the former Miners' Offices on Saltergate. They

both started work as ten year olds in the harsh circumstances of the mid

19th Century at collieries at Clay Cross and Grassmoor.

Later they became active as both methodist lay preachers and trade

unionists. In time they came to feel that north Derbyshire needed its

own mining association separate from the rather distant South Yorkshire

Miners Association which they had been active in until then.

Along

with three other miners, in 1879 they met at the old Sun Inn on West

Bars (which preceded the current building) to plan to set up the

Derbyshire Miners' Association (DMA). James Haslam became the DMA's

first secretary, initially being unpaid and running the Association from

his home. By 1893 it had 10,000 members in 69 local lodges and was able

to open its offices on Saltergate that year. Haslam and Harvey became

known as 'The Twin Pillars of the DMA”.

For some time in the 19th

Century, Parliamentary representation had been seen as a must by mining

trade unions. They needed legislation to check that they weren't

cheated over payments for the amount of coal they produced, to improve

safety conditions, to end the employment of children, to reduce

excessive working hours, to seek minimum wages, to set up conciliation

procedures and to regulate the structure of their industry. There was

also a deep need to improve housing, education, health and social

provisions within their communities.

But

there were three major hurdles to overcome in order to get miners into

parliament. First, although many miners as male householders had first

achieved franchise rights in 1884 , they needed organising to ensure

that they were registered to vote. The system for registration was not

then an easy one. So when Haslam stood as Independent Labour in 1885 in

Chesterfield, he finished bottom of the poll in a three cornered fight.

There had not been time in just a year to mobilise the registration of

enough miners. Secondly, MPs were not paid and had the costs of travel

and accommodation in London to meet. It was not until 1901 that the

Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) to whom the DMA were

affiliated, came up with a modest scheme to cover these needs for

successful mining candidates. Finally. to win a candidate needed the

backing of one of the main political parties of the 19th

Century – the Conservatives or the Liberals. The embryo Labour Party

wasn't set up until 1900 and at that time the MFGB was not even

affiliated to it.

So

after his initial electoral defeat, Haslam backed by the DMA sort the

Liberal nomination. When he narrowly failed to achieve this he bided his

time until the candidature became vacant once more. He was then

successfully elected to parliament for Chesterfield in 1906 supported by

both the DMA and the local Liberal Association and was known as a

Lib-Lab candidate. In a 1907 by-election in what was then called North Eastern Derbyshire, William Harvey also won as a Lib-Lab.

In

1909, however, the MFGB (covering the DMA) affiliated to the Labour

Party and Haslam and Harvey accepted the Labour whip, standing

successfully in the next two elections of 1910 as Labour candidates.

We

could then have expected there to have been a seamless transition to

the ranks of the Labour Party by the DMA and its candidates. If we

ignore what happened in the Chesterfield seat this is exactly what

occurred in the two neighbouring seats. Both ran a number of DMA

candidates under the Labour banner. But they did not initially win their

seats. There were no further Labour victories by a miner until Frank

Lee (at his second attempt) took the North East Derbyshire seat

following the 1922 General Election , but only after a drawn out

procedure. There were eight recounts, then the matter went to the courts

and only seven months later was Lee able to enter parliament after

finally being declared the winner by 15 votes. He held his seat until

his death in 1942, apart from the 1931-35 period when Labour collapsed

nationally following the consequences of the 1931 financial crisis.

Lee

was a solid Labour man in parliament involved in issues such the

Miners' Lock-Out of 1926, its associated General Strike and criticism of

the break-away Spencer's Miners' Union in Notts which was seen as a

“scabs union”. He also worked hard on the wide range of communal

concerns in his constituency. But although Lee stood in seven General

Elections as a Labour Candidate and won five times, like Haslam and

Harvey his early political involvement had been of a Lib-Lab nature and

he had even been a local Liberal agent.

But

whilst Haslam, Harvey and Lee moved away from the Liberals to the

Labour Party, there was one official of the DMA who finally moved in the

opposite direction – Barnet Kenyon. On the death of Haslam in 1913 he

became the Secretary and then the Agent of the DMA. The DMA supported

him to stand for the Chesterfield seat and he was then endorsed by the

Chesterfield Trade Union Council, which in those days also fulfilled the

role of what would now be a Constituency Labour Party. But when Kenyon

then agreed to address the local Liberal Association at their annual

meetings and accepted their support in the coming by-election, the MFGB

Annual Conference spent a whole day discussing his case and then refused

to endorse his candidature. The Labour Party's Executive Committee also

rejected him. Kenyon ended up as the Liberal Party Candidate and held

the seat as such from 1913 until his retirement in 1929. The DMA finally

removing Kenyon from his post as their Agent in 1923, around the time

Lee was finally able to take his seat in parliament as a Labour MP.

Essentially

the DMA had moved from the Lib-Lab to the Labour camp in 1909, except

for the strange case of Kenyon in Chesterfield. A complexity about the

Chesterfield seat being that it was not as solid a mining area as its

neighbouring seats, which eventually became designated as

Bolsover and North East Derbyshire. Chesterfield was less homogeneous,

for alongside mining it developed Chemical and Steel works at Staveley,

plus engineering works and a range of commercial and business

institutions. It was a town, distinct from the surrounding rural areas

which were pock marked with pits. Between 1913 and 1964 it did not have a

mining MP, which was normally a contrast with its two neighbouring

seats.

Nevertheless

Chesterfield became a centre for the DMA. The statues of Haslam and

Harvey were unveiled in 1915 after their deaths, with thousands of

miners and their families from the wider coalfield being crammed in

front of the Miners' Offices on Saltergate.

Chapter 12

In

the previous chapter, I dealt with ten North Derbyshire parliamentary

pitmen politicians who were all members of the Derbyshire Miners'

Association. All of these became Labour MPs, except Barnet Keynon who

was exclusively a Liberal. The nine miners, who were Labour MPs, have

been matched by nine fellow MPs who were not miners. I deal with these

below.

Between 1922 and 1944, the then Clay Cross Constituency

was represented by four Labour MPs who were not miners - Charlie Duncan

1922-33, Arthur Henderson 1933-5, Alfred Holland 1935-36 and George

Ridley 1936-44. Each of them died when MPs. Although Clay Cross covered

more prominent mining areas than any of the North Derbyshire

Constituencies at that time, they opted for 22 continuous years of

having these non-mining MPs. I gave details about the Clay Cross

Constituency in Chapter 5, in which I gave reasons as to why they

endorsed non-miners.

Three of the areas non-mining MPs have

represented the Chesterfield Constituency - George Benson 1929-31 and

then 1935-64, Tony Benn 1984-2001 and Toby Perkins since 2010. I deal

with each of these each in turn below.

George Benson had been

imprisoned as a conscientious objector during the First World War,

became Chair of the Howard League for Penal Reform and was knighted. He

had a left-wing background, at one time being Treasurer of the

Independent Labour Party.

Tony Benn was first elected locally in

a famous by-election in Chesterfield in 1984, just prior to that year's

miners' strike. It was a contest which attracted a then record number

of 17 candidates. He had been the MP for Bristol South East for two

periods between 1950 and 1961 and then from 1963 to 1983, until the seat

was abolished. His break as their MP between 1961 and 1963 arose

because he inherited a seat in the Lords, but he successfully campaigned

to allow people to reject their elevation to the Peerage; a matter that

was passed into law in 1963. He held Ministerial Office during the

periods of the Wilson and Callaghan Governments, moving to the left in

the Labour Party in the late 1960s. He narrowly failed to beat Dennis

Healy for the Deputy Leadership of the Labour Party in 1981. So, by the

time he arrived in Chesterfield he had become something of an icon for

the Labour Left. He went on to stand unsuccessfully against Neil Kinnock

for the leadership of the Labour Party in 1988, losing by a substantial

margin.

Tony Benn

Toby

Perkins re-captured the Chesterfield seat in 2010, after it had been

held by a Liberal Democrat for nine years. Overall, Labour lost 91 seats

in that general election, so the gain of Chesterfield was quite an

achievement. In his short time as an MP, he has served as a Shadow

Minister for Education and is currently part of the front-bench team for

Business, Innovation and Skills.

Toby with Ed Miliband

The

Labour MPs for North East Derbyshire (under its different shapes and

guises) were exclusively miners until 1987. The pattern started up in

1909, when William Edwin Harvey moved from the Lib-Lab camp to Labour.

Although Labour lost the seat between 1914 to 1922 and 1931 to 1935,

there was a total of 70 years in which the seat was held by miners.

These were Harvey, Lee, White, Swain and Ellis. I was the person who

broke this fine mould. In mitigation, I can only point to my close links

with the Derbyshire Miners. I had taught politics with classes of

miners on day-release classes from 1966 to 1987. A summary of my own 18

year parliamentary career is contained in a 12 page document entitled "A

synopsis of my time as an MP", culled from 121 detailed reports which I

issued over that time to the North East Derbyshire Constituency Labour

Party.

In parliament Dennis Skinner, Tony Benn and myself fought

against the continuing and final closure of Derbyshire's pits, but by

the time I retired in 2005 the area had moved into a new era. The pits

had gone. Up to then what had been the coal mining area of North

Derbyshire had been served by a total of 17 Labour MPs; yet not one of

these was a women. This was despite the fact that all of the

Constituencies in the area had been served by powerful female activists

such as Ethel Lenthall, Dot Walton, Thelma Lide, Jill Jones and Florence

Hancock (in reference to the latter, who operated in the Clay Cross

Constituency, it is stated "it can be literally said that Florence

Hancock won Clay Cross for Labour.") In part, the lack of female MPs can

be explained by the prominent role of the mining industry.

Harry Barnes

The

situation was only finally rectified in 2005, when I was succeeded by

Natascha Engel. She had worked as a volunteer in Spain with Amnesty

International, as a trade union political fund co-ordinator and as

Director of the John Smith Institute. In the Commons her first

parliamentary positions were those of Parliamentary Private Secretaries

and as a member of Select Committees. From 2010 she has been Chair of

the pioneering Back Bench Business Committee, directly elected to the

position by her fellow MPs. In 2011 Natascha was "Backbencher of the

Year" and in 2013 the Political Studies Association www.psa.ac.uk named her as "Parliamentarian of the Year".

Natascha with Dennis Skinner

In

the Labour interest, our area of Derbyshire is now (when this was initially published) served by Dennis

Skinner, Toby Perkins and Natascha Engel. They represent the current

stage of a journey pioneered by James Haslam and William Harvey whose

(newly cleaned) statues can be found outside of the former Miners'

Offices on Saltergate in Chesterfield. It is a tradition continually to

be built upon.

|

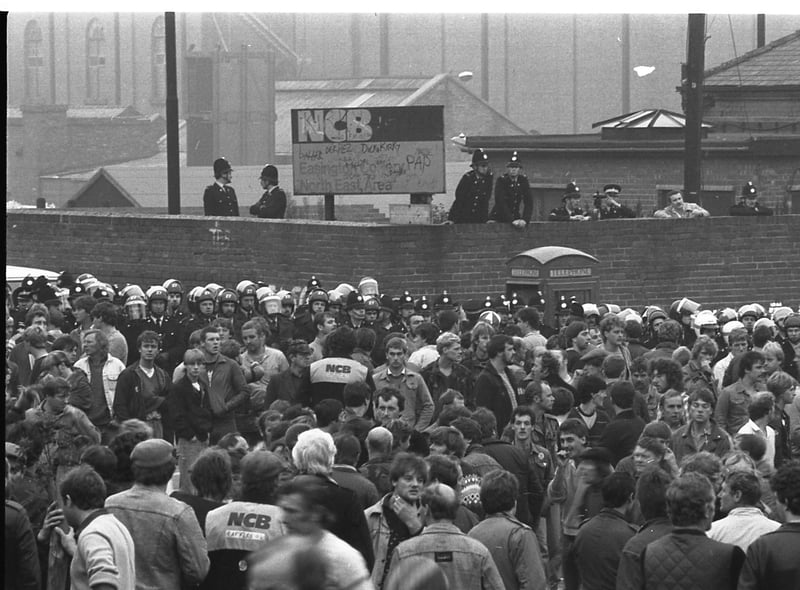

1984/85 Miners Strike at Easington - on a visit to my parents I joined them.

1984/85 Miners Strike at Easington - on a visit to my parents I joined them. Ignoring those who acted as temporary leaders of the Labour Party for short transitional periods, there have been 12 full-time leaders of the Labour Party in my lifetime.

Ignoring those who acted as temporary leaders of the Labour Party for short transitional periods, there have been 12 full-time leaders of the Labour Party in my lifetime.